For small and minority farmers, networks influence the bottom line

June 3, 2020

“Small-scale and minority-owned farms don’t always have the same access to external resources that larger farms do, so they often rely more heavily on their internal or social networks for information and resource sharing,” said NERCRD Director Stephan Goetz. “Our research shows that this networking pays off, in terms of their sales. Farmers who added a single new connection to their network experienced up to a 25% increase in sales.”

The research was carried out in three phases, according to the study’s lead author, Aditya Khanal, assistant professor of agricultural economics in the College of Agriculture at Tennessee State University.

“First, we identified the networks themselves in the communities–how do the farmers cluster, how likely are they to network with one another, for example, for agricultural production and marketing advice and sharing resources? Then we identified which of the farmers were most central to the network, which indicates the relative importance of each farmer to the network,” Khanal said. “Last, we tested whether being central in the network influences individual farms’ economic performance.”

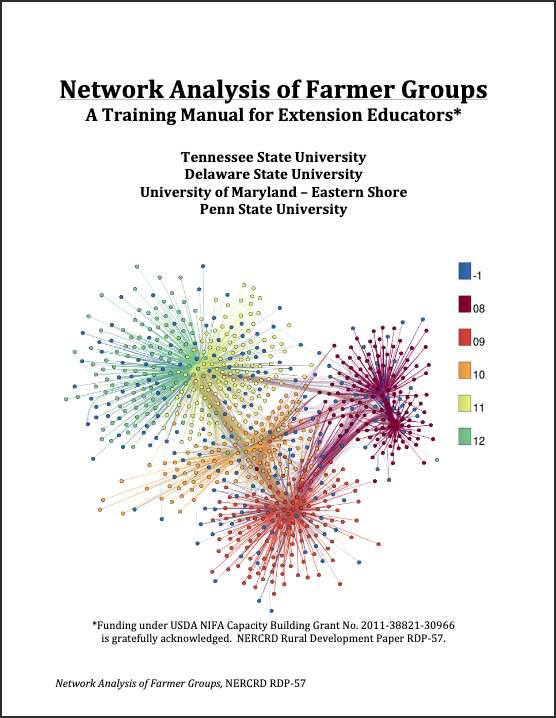

To identify farmer networks, research team members from Tennessee State University, University of Maryland-Eastern Shore, and Delaware State University worked with their respective Cooperative Extension units to identify small-scale and minority specialty-crop farmers in each of their states. In turn, those farmers were asked to identify additional farmers in their networks.

The resulting group of farmers, 117 in three states, were surveyed to obtain information for the network analysis. Farmers answered questions about the nature of the relationships in their network, such as “Among these farmers, which one would you go to for information about a production problem?” and “Who do you ask for advice on how to apply for credit, or file taxes?” They also answered demographic questions and questions about their farming plans, production and sales.

The researchers then conducted an analysis aimed at identifying each respondent’s position in their respective network, a concept referred to as “network centrality,” which is calculated by examining how members of the network relate to one another. “Degree centrality” measures the number of connections each farmer has with other farmers, including outgoing connections they initiate by reaching out to someone (degree-out centrality), and incoming connections initiated by others (degree-in centrality). “Closeness centrality” measures how quickly or directly a member can communicate with other network members without having to go through other members. The higher an Individual’s closeness centrality, the more easily that individual can contact others within the network. “Betweenness centrality” measures the extent to which each farmer serves as an intermediary between other farmers in the network.

“Depending on which of these centrality measures we choose, we can get different information about how each farmer fits into his or her network,” Goetz said. “For example, people with high degree-in centrality–those who have more people seeking them out–enjoy more popularity within the network, while people with high betweenness centrality often control the flow of information in the network. They decide who hears what information, or receives different tips about production or marketing practices.”

Using statistical techniques, the researchers examined the effect of each of these centrality measures on farm performance. While each measure was found to be positively and significantly related to farm sales, they differed in terms of the strength of the effect. For example, farmers whose degree-in centrality increased by one new connection saw a 19 percent increase in their farm sales, according to the researchers’ model, while a farmer whose degree-out centrality increased by the same amount saw a 25 percent increase in sales.

“People who have stronger connections–at work, in society, with friends–have advantages,” Goetz said. “They may be more gregarious and more easily make contacts, and therefore also have more access to information. It’s not difficult to imagine how this would translate into an advantage in terms of greater sales for a small-scale vegetable farmer.”

For example, Goetz said that connecting with other farmers could help an individual acquire knowledge about new market opportunities, learn about new technologies that increase production efficiency, or gain access to farm-related information such as a new crop variety, all of which could enhance sales.

The researchers also examined the extent to which demographic and socio-economic factors influence a farmer’s position in the network, and found that older, more educated farmers had higher centrality positions in their network than their younger, less educated peers. They also found that male farmers had higher degree-out centrality than females, suggesting that female farmers are less likely to reach out to other farmers than males.

The research team, which reported their results in the Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development on April 17, 2020, also produced a training manual to help agricultural support organizations conduct their own network analyses. By identifying and characterizing farmer networks, organizations can more effectively disseminate information by targeting those farmers who have greater centrality and are more likely to share it with other farmers.

Goetz said in future research, he and his colleagues will study other economic and social networks in order to better understand how effective networks are best organized.

“The idea of a social network analysis is to eventually compare different networks and to see what makes them effective. We can look at how or why or whether individuals in a given network are more effective, depending on their position within the network, and we can also look at whether different network structures are more effective than others.”

In addition to Goetz and Khanal, other members of the research team include Fisseha Tegegne, (professor of agricultural economics at Tennessee State University), Lan Li (formerly at Tennessee State University and now an economist at Food and Agricultural Organization, FAO of the United Nations), Yicheol Han (formerly at Penn State and now at the Korea Rural Economic Institute), Stephan Tubene (University of Maryland-Eastern Shore) and Andy Wetherill (Delaware State University).

The research was funded by a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Capacity-Building Grant (TENX-2011-02563, Grant#2011-38821-30966).